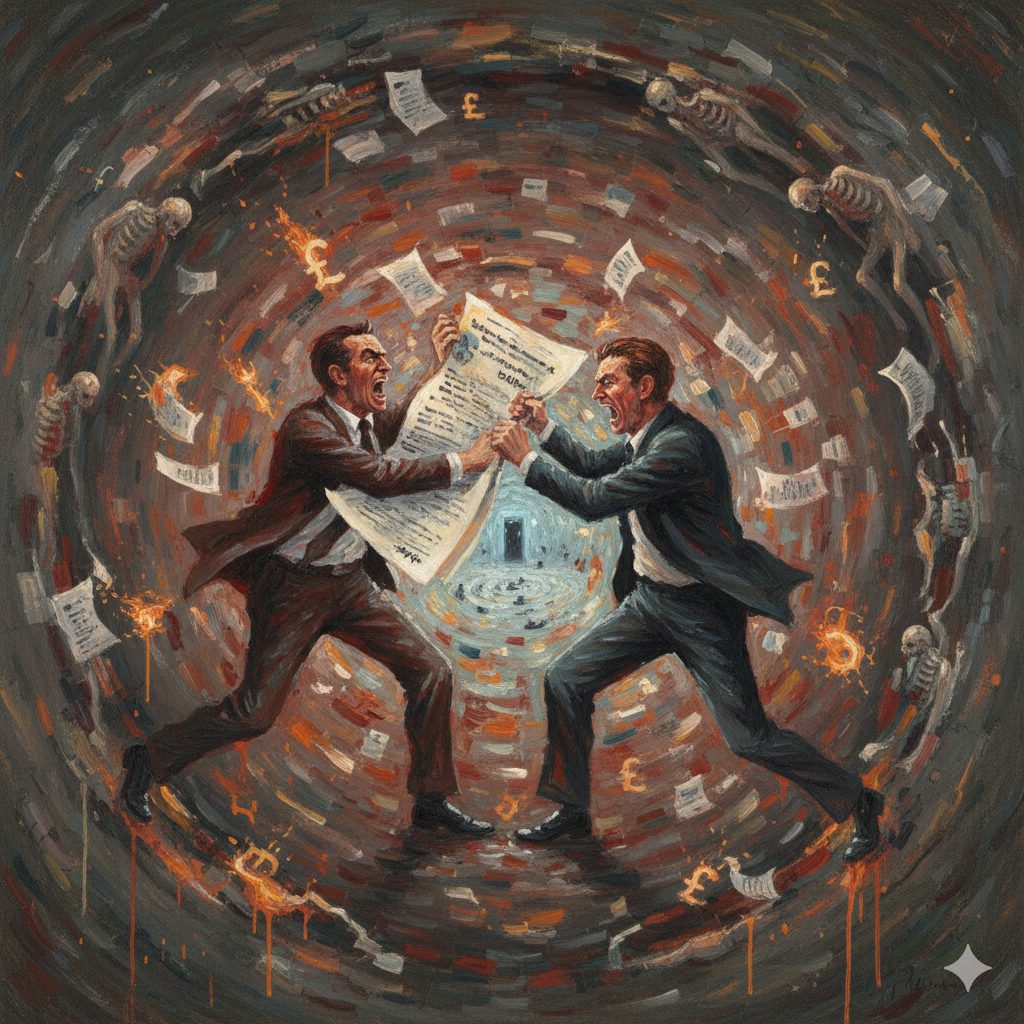

Greggonomics 13: The Nine Circles of Hell

I’ve been carrying the idea behind this piece around since I started Hunt ADR almost a decade ago. Some ideas need time, the right audience and the right vehicle. For me, there is no better place to run an idea like this properly, and take it all the way to where it naturally leads, than Greggonomics. So here we are.

Dante Alighieri’s Inferno is usually taught as a catalogue of sins, neatly arranged and morally labelled. I’ve never found that the most interesting way to read it as what stayed with me isn’t the punishment, but the sense of options narrowing as Dante descends.

Each circle is worse than the last, but more importantly, each one is harder to leave. Choice diminishes and agency fades and by the time Dante reaches the bottom, Hell is no longer dramatic or chaotic, it’s cold, static, and final.

The longer I’ve worked with disputes, the more familiar that structure has started to feel. Very few businesses set out to end up in entrenched, value-destroying conflict. Nobody decides one morning to sacrifice time, money, relationships, and focus. What usually happens instead is a series of small, reasonable decisions – each defensible on its own – that quietly narrow the available exits.

Most disputes don’t explode, they rumble on behind the scenes and and at some point, usually much later than anyone realises, someone says: “We don’t really have any choice now.”

That moment really matters.

Limbo

Every dispute starts here, although it rarely looks like a dispute at the time. An invoice hasn’t been paid and an email hasn’t been answered; a contractual obligation feels a little more flexible than it probably should. We’re British so everyone remains polite – no one wants to overreact. Limbo feels sensible and proportionate, which is precisely why it’s so easy to stay there.

What often goes unnoticed is that assumptions begin to diverge, evidence quietly degrades, and risk accumulates without being acknowledged. Nothing is resolved, but something is clearly forming in the background.

Lust

Somewhere along the line, emotion creeps in – usually quietly and unoticed at first.

Maybe an email is misinterpreted as the recipient rereads it and hears a different tone than the sender meant (we have all been there!). Another person is copied in “just for visibility”. Passive aggressiveness is simering and whilst nothing openly hostile happens, the temperature changes.

Interpretation starts to matter more than content and the silence begins to feel pointed rather than neutral. Motives are inferred rather than clarified while at this stage, the dispute is still entirely manageable, but commercial judgment is now sharing space with ego, and that balance is rarely obvious to the people involved.

Gluttony

By now, the story has started to grow. Colleagues are briefed and advisors are consulted. The narrative is told, retold, and refined. Each version adds a little more certainty and a little more edge. Facts begin to serve the story rather than challenge it.

What grows fastest here is not understanding, but confidence – the quiet conviction that “we are clearly in the right”. By the time things reach this point, the dispute already feels bigger than it actually is.

Greed

At some stage, proportionality begins to slip, although it rarely announces itself clearly.

Compromise starts to feel unappealing and bullishness and ego make settlement sound suspiciously like weakness. The question shifts from “What would resolve this?” to “What can we get out of it?”, even if no one would phrase it quite so directly.

Positions harden as concessions stop being something to exchange and start being something to bank. The dispute becomes less about the underlying issue and more about what backing down might imply. Once that happens, resolution becomes emotionally expensive, even when it remains commercially sensible.

Wrath

By this point, the conflict is usually formal, although it is still wrapped in polite language.

Legal correspondence appears and positions are asserted rather than explored. Communication becomes strategic and silence becomes tactical.

This is where relationships – commercial and personal – begin to suffer in ways that don’t always repair cleanly, even if the dispute eventually settles. You can still get out from here, but it will no longer be painless.

Heresy

Eventually, the parties stop talking about quite the same dispute. Each side has built its own internal version of events, reinforced by selectively accepted advice and carefully curated evidence. Confidence replaces curiosity as doubt becomes inconvenient.

This is usually where people stop asking themselves the most uncomfortable question of all:

What if we’re wrong about some of this?

From here on, the descent tends to accelerate.

Violence

Not violence in the physical sense (though I have seen it), but in consequence.

Costs escalate and management time drains away. Internal morale dips and if you are not careful external perceptions shift. Opportunity costs accumulate quietly in the background.

Even if someone technically “wins” at this stage, the business itself has already taken a hit – often one that never quite shows up on a balance sheet.

Fraud

At this point, the dispute no longer needs fuel. It runs on inertia. Process begins to matter more than outcome. Each procedural step justifies the next as sdvisors manage exposure rather than direction. Momentum replaces intention.

Ask most people involved at this stage what a good ending would actually look like, and you’ll often get a pause rather than an answer.

Treachery

Dante’s deepest Hell isn’t fire. It’s ice. Here, outcomes are imposed rather than chosen. Relationships are irreparably damaged. Everyone is disappointed – including the party that technically “wins”.

This is usually the point where someone finally says there is no choice left, without noticing how long ago choice slipped away.

What This Has to Do With ADR

One of the persistent misunderstandings about dispute resolution is the idea that it sits at the end of the story. In reality, dispute resolution is about deciding where the story stops.

Mediation works best when there is still flexibility – when parties can still hear risk, imagine alternatives, and retain a sense of control over the outcome. Used properly, it isn’t about concession; it’s about agency.

Arbitration tends to come later, when positions are fixed but parties still want expertise, confidentiality, and an end point that isn’t public theatre. What arbitration is not, though, is the bottom of the descent. It is a decision to stop before disputes freeze into something colder and more damaging.

The real failure in dispute management isn’t losing. It’s letting a dispute run on long enough that the ending is no longer something you actively choose.

At that point, the question is no longer legal. It’s about governance, judgment, and timing.

The Last Word

I try to finish each Greggonomics with a quote, and there is really only one line from Dante that belongs here – the warning carved above the gates of Hell itself:

“Abandon all hope, ye who enter here.” Dante Alighieri, Inferno

Dante wasn’t talking about drama or punishment. He was describing what happens when choice disappears.

Most long-running disputes don’t become damaging because anyone is malicious. They become damaging because hope drains away – hope of resolution, of being heard, of getting back to the business of actually running a business.

By the time people feel they have “no choice left”, they are usually much deeper than they realise.

Our job in 2026 is not to lead people through the gates. It’s to notice when they’re approaching them – and help them turn back while they still can. Because the real failure in dispute resolution isn’t conflict. It’s surrendering agency without noticing you’ve done so.

See you next time, Gregg

This article was originally published as an edition of the Greggonomics newsletter on LinkedIn. To receive these updates directly to your inbox and join the discussion, you can Subscribe on LinkedIn or join Gregg’s dedicated community over on Substack.